Asinine Building Blocks of the Demented Coward

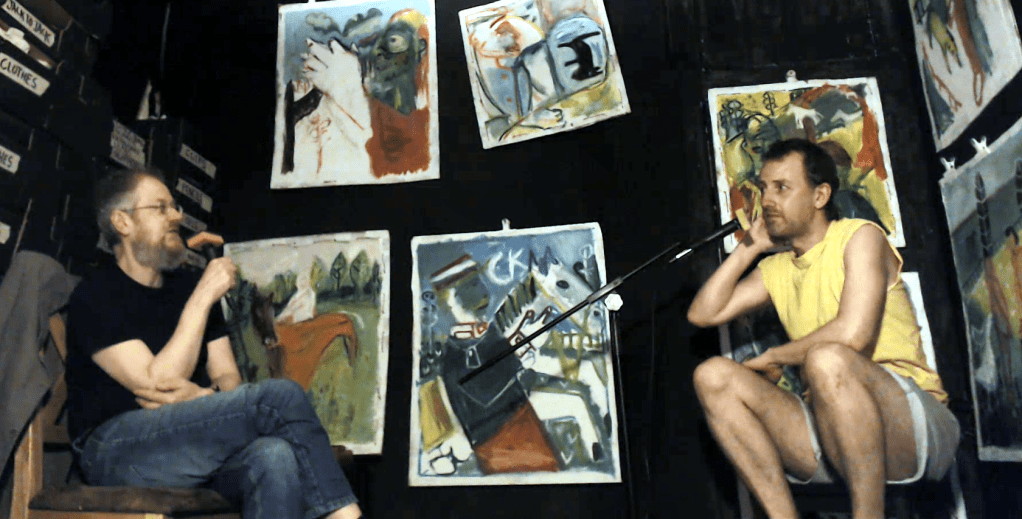

Me a Doll interview. 25th April 2024. Emma Pugmire interviews Me a Doll (aka Edgeworth Johnstone) at Black Ivory Printmaking & Audio Club, London, UK.

MAD: Before we start, Me a Doll’s are heavily influenced by Neo Heart’s The Fembot Oracle.

PUG: And now to start the interview. How do you make the Me a Doll’s?

MAD: It’s different to how Neo does it. I don’t know exactly what he does but it involves a photography technique I don’t know much about. My method’s beginners level GIMP, which is like free Photoshop. The source images are stills taken from nude self-portrait dancing like cigarette smoke videos I made in Black Ivory superimposed over each other. There’s way less digital editing than I think it looks. Just 4 or 5 commands repeated however many times, then chopped in half and made vertically symmetrical, I guess like Neo does.

There’s also this varying contrast with horizontal bands, like the stripes on the sides of the Jompiy paintings.

PUG: What are the contrast bands?

MAD: It’s where I couldn’t get a level that worked for all parts so I divided it up like the Jompiy sides. You have to view Jompiy by slow hand rotations. They’re 3D sculptures.

PUG: Where do the names ‘Jompiy’ and ‘Me a Doll come from?

MAD: ‘Jompiy’ sounded and looked right. Pure Aesphonly.

PUG: What about ‘Me a Doll’?

MAD: In the first one I look like a doll. The first of the experimental’s, but I also like it sounding like ‘Me Adult’. It’s said that art’s re-learning what you knew as a kid. Making Me a Doll’s is what a kid might do. You know how ripping people off’s generally seen as a bad thing? Like copyright or stolen valour. And how kids couldn’t care less. It’s me as an adult taking direction from me as a kid, not you as an adult. Kids don’t worry about who did what, they just do what they want and have no problem being honest about it. And can’t understand why anyone else would have a problem with it. They haven’t had the territorial greed educated into them yet.

PUG: You didn’t want to make them different, but loosely inspired by the Fembots?

MAD: I wanted to make them like a kid wants to draw Mickey Mouse. Not their own interpretation. I want to draw Mickey Mouse like Walt Disney did.

PUG: You’ve divided the Me a Doll’s into two categories. The experiments and then the final series. When did you know the experimentation was over?

MAD: After about fifteen that were more like deviations. Then it was back to the carbon copy attempts for the final series. The experimentation was as much getting comfortable with the software as anything else.

PUG: Going from painting figuratively into more abstract and digital art is quite a change in direction. What led to it?

MAD: It’s just the natural tides of what you end up doing, when you don’t do the same thing all the time. Every so often you come across work that makes you sit up and go galloping off somewhere. Fembot led to Me a Doll. With Jompiy it was a co-worker at Wave running an art class on salad spinner spin paintings she saw on Instagram. It’s like being jumped on and having your cataracts torn out. Like when I first heard Nirvana, it wasn’t ‘I really, really like this song. This is my new favourite band.’ It was incomprehension. Going through the Fembot Oracle led to a similar re-evaluation of visual art for me. I had them strewn out over the floor and knew it would lead to something massively different to what I would have guessed I’d be doing next. Then the same again when we started making the salad-spin paintings at Wave. It’s like ‘Shelve everything else. I’m doing this now and for the foreseeable future. Maybe see you in a couple of weeks.’

PUG: Would it be fair to say you’ve moved away from the Stuckist idea that figurative painting is the medium of self-discovery?

MAD: I don’t know about self-discovery. Art can get tied up in stuff like that if people want but my paintings aren’t anything to do with learning more about myself or any psychological therapy, introspection and all that. It’s not about serving society and making the world a better place, or a lot of what’s in the Stuckist manifesto. I couldn’t care less about anything that’s essentially ‘the outside world’. It’s often like painting feels obliged to justify its reason for being and have some sort of use, or provide some sort of service. Art doesn’t need to explain itself or do anything for anyone. I’m not really much of a Stuckist if you’re talking about the manifesto. Probably why I keep writing my own for The Other Muswell Hill Stuckists. I’m not a Stuckist, I’m a The Other Muswell Hill Stuckist. We’re not as similar as you might think. Not you, obviously, but you know.

But about painting and self-discovery whereas conceptual art blocks access to inner worlds, I don’t think it’s true anyway. It’s just a perspective that could just as much be reversed. Stuckism ignores The Theory of Relativity. Not that I know what The Theory of Relativity is but judging by the title, a big Stuckist missed opportunity to have been even funnier, I think. I think things are funnier when they’re true. Especially in art where you’ve got everyone trying to take it all so seriously and put things on a pedestal. Anyone can project what they want onto art, join whatever dots and convince yourself you’ve worked it all out. People do it all the time. Enough make a living out of it, but I find it all just so rubbish and dull to join in with. Pretending you can tell good from bad when it’s all just perspective, your tastes, maybe down to what you had for breakfast. There’s no facts in art.

PUG: For you, it depends on the individual.

MAD: It’s “I don’t like conceptual art. So what?” Dada vs Expressionism, so what? Stuckism vs Conceptual art. The big to-do around Guston going figurative. It’s like green’s my favourite colour, you know. People that like blue are wrong because it’s cold and primary. It lacks the complexity, the emotional intellectual depth of green. Green’s a special blend of primaries working in symbiotic harmony. Relationships, conflict and ultimately, resolution mirroring the human condition, finally at one with itself. Green contains no red because red means danger in nature. It’s a warning suppressed in our feral being, elevating green above both orange and purple. Orange and purple represent conflict and war. Green’s the nirvanay reward for the intrepid artist who dares take risks at the expense of commercial success. All my paintings are green. There’s nothing else in them, just green. Primary colours block access to inner worlds. They’re juvenile, bright and shallow immature sugar-rushes. Asinine building blocks of the demented coward. Would you rather have a house, complete with bathrooms, at least one kitchen and a garage, or a brick? People that like blue lack the sensitivity, vision and understanding people that like green have. They’re lost in a cul-de-sac of idiocy. Actually, brown’s the best colour because it has all the primaries and therefore allows for a more holistic and unfragmented appreciation and range of human experiences. Although, on the down side, it’s the colour of shit. But let’s park that to one side for a moment and take the time to wonder at its splendour. To look inward and discover ourselves through the appreciation of brown. You say “shit”, we say “chocolate”! Ben Shapiro said words to this effect about classical music’s superiority to pop. It’s hysterical because he’s being totally serious. Actually, there was a better one from around the 1950’s on American TV where this bloke was laying out the case for jazz being superior to, and more sophisticated than pop. Suit and tie, short back and sides, looking like a newsreader. He had one of those velvety deep Orson Welles voices that made everything he says sound clever. All his ducks in a row. All logical and water-tight. Sounded great apart from being complete nonsense.

Must have been equally great for Picasso, having an esteemed critic like John Berger telling him his paintings needed themes, and that this is where his recent work had faltered. A fully educated and qualified art critic, no less. Telling Picasso where he’s going wrong with his paintings. A shame Berger couldn’t have painted a few of his own, to show Picasso precisely what he meant.

The problem with words and art is that words are like these big fat clumsy fingers trying to pick up atoms. Like trying to get to a number with fifteen after its decimal point using only five and ten. You can spend all day going round the houses but you’re never going to get there. It’s the wrong tool for the wrong job.

PUG: These rabbit holes you go down with things like the Fembots, they seem to act as a catalyst for your next project.

MAD: It’s like when I first saw your work, when you pull out these postcards at Stuck in Wood Green, or Luminosity, or reading ‘Monsieur Tourette’ and thinking ‘I’ve got the work for this.’ The Fembots were another example of ‘This is happening like this, with or without anyone else.’ Tuning into the Ron Throop studio and not having a clue what you’re about to see. Fembots have that spirit about them.

PUG: What paint does Jompiy use?

MAD: It’s the cheap tempera they have in schools. The solid parts are Lascaux Artists acrylic. £180 for four tubes but the other stuff didn’t work. Instead of the tempera, I could have got this acrylic and fluid medium but it’s like with expensive oil paint and looking too blingy. Like we were talking about on our weekly Instagram Live broadcast that starts at 8PM GMT every Thursday on account edgeworth.blog, I’m better off with the cheap oil paint. The expensive ones have too much pigment. The opposite being true of acrylic.

PUG: Do you like the accidental? That it’s unplanned and you don’t know what you’re going to get.

MAD: Sometimes, but you never know. If I only properly get involved at a later stage it opens up another load of options because I’m starting off on the wrong foot. With Me a Doll I’m working into an existing form from the start because the beginning phases are pretty much automatic, just with different poses and starting colours. It’s different from a plain white surface then straight into hand eye control.

PUG: So it’s like the starting point sets you off in another direction.

MAD: And then other things stem from those and so on, repeatedly. I’ve always got these different projects like Aesphonly, Jompiy, Heckel’s Horse Jr., all spawning from different parent activities. The wider you cast all these projects, the wider the scope of what you can get out of it. Me a Dolls, like the masks could be paintings, posters, videos. I’ve started a set of these A4 red carbon paper line drawings from the Me a Doll printouts. One thing leads to several others. Art begets art.

Time feels short when you consider these things and where everything can go. Why I’m so keen to build Black Ivory. I need a hub that relates it all, and us all together. The Emma Pugmire section. There’s Charles and Ron. Ron and I have collaborated his words into my woodcuts. Billy and I collaborate, which connects to Heckel’s Horse Jr.

Charles and I have done a few joint paintings. Me a Doll’s probably as close as you can get to collaboration. You and I are in a band. Rose singing and harmonica, Ron on guitar, then we have a go, then Charles reads his poetry. Ron does another book for which I paint the cover. We record another album in the studio Billy and Huddie record theirs, for which Ron does the cover. It’s this incestuous passive income you get from just being in and amongst other people’s work and the seemingly infinite spin-off’s each individual movement has. Even within Jompiy, each series relates to every other. One has the masking tape from another. One uses excess paint scraped or smudged from another.

PUG: Was that the reason for starting Black Ivory?

MAD: At first, I didn’t envision Black Ivory being anything beyond a print club. But it started looking like a brand that finally relates to what I do and suits what goes on here. The Stuckists are anti-anti-art. The Other Muswell Hill Stuckists are indifferent-anti-art. Heckel’s Horse is a side project. Heckel’s Horse Jr.’s a side project of a side project. We’re not an Indie Rock band but we’re nothing closer, so let’s make something closer ourselves. A well-fitting common denominator.

There needs to be a collective noun, if that’s what it’s called. Is it abstract noun? Like weddings and car boot sales. Nouns you can’t touch. They had a term for it at school. Whatever it is, there needs to be one for us. And now there is, Black Ivory Printmaking & Audio Club. A roller-off-the-tonguer for our bit of the Venn diagram. We just needed a name and a website. Glance at Black Ivory and you get a sense of our work. Glance at any of the other groups or partnerships I’m involved in and you get 5% at best.

PUG: A place to keep it all together.

MAD: Our lonely wandering icebergs have crashed into each other and we now join forces in sticking this elephant flag in the snow and proudly declare our newly formed nation ‘Black Ivory Printmaking & Audio Club.’

About that cross-pollination thing, Black Ivory did a Jasmine Surreal exhibition and interview. Years ago Shelley and I went round hers, like around 2010 and filmed her cat puppets, and then there were these videos she and Charles did at this other place in East Finchley where these student film makers called ‘Pleb’ set up this, what looked like disused office spaces. At her flat, after when I was editing, I put a song I recorded with this singer over the top, then Jasmine and I performed at ‘Pleb’ this singing and morphed guitar Charles said was words to the effect of near-hypnotically mesmerising. I think Jasmine was playing guitar and singing abstract noises, as far as I’m aware the first time she’d ever held a guitar. I was knelt on the floor morphing the feedback. I don’t know if Charles has the footage.

PUG: Looking at the Me a Dolls within your other work, do you think there’s such a great division between abstract and figurative?

MAD: Me a Doll‘s end up figurative but when I’m doing them they’re just shapes and colours that need creating and correcting. Same for all my work really. Jompiy’s look abstract but are figurative. A table’s 99.9% gaps between and within atoms. I’m a figurative artist whose works are 99.9% abstract. My lyrics are just abstract phonetic noises that get shoe-horned into whatever the best fitting words are. It’s only the abstract aspect of it that I think matters. Anything else is either just distraction or an excuse for the music being bad, so I try to avoid giving them any too clear meaning. There’s nothing worse than a great lyric, but then a completely meaningless string of arbitrary words would be just as distracting. It’s why I tend not to like symbolism, humour, politics or satire in art. It all comes across as a bad excuse.

PUG: What did Neo think when you showed him the Me a Dolls?

MAD: I guess what I did. I don’t know, but essentially positive and interested. Everything I hoped. Then I went home and made a load more.

PUG: Inspired?

MAD: Yes, but I’m not sure what difference being inspired makes. As long as you start. Artists worth their salt shouldn’t need inspiration. Ron and Rose visit from Oswego, then comes a painting binge. Or Monday’s at Billy’s. If I’m in music mode, for example, then I go to Chatham as a weekly reminder that I’m still a painter. Talking with Neo about the Fembots and Me a Doll solidified some ideas and led to, what could be a Me a Doll video, or a Me a Doll painting. But it’s not like otherwise I’d have done nothing, or even something lesser, necessarily.

PUG: Do you think there’s a big overlap between these methods and your music?

MAD: Yes, it’s all the same thing in different forms.

PUG: How does it feel going from making paintings to using digital technology?

MAD: I get sick of one, switch to another till I get sick of that. They must use different parts of the brain and burn up different attention spans. I rarely paint all day, for example. It’ll be a couple of hours. But Elbow Sisters videos like Gan Mao, Like I Need it Now, Tian Tang, Wu Li An Le and probably a load others took ages. We’d have recorded a song within an hour of me writing it, then five straight hours editing the video. I was writing songs almost just so I could make the video.

PUG: There’s been a lot of fuss online about AI and digital art recently, and what it means to painters, musicians etc. Do you agree that digital art’s a threat to painting?

MAD: It’s only a threat to shit painting. But not even that, it’s just something else to do. Like making pasta or watching Hollyoaks. It’s like saying Conceptual Art’s anti-art. I just see it as not-art, which is no criticism. There’s this assumption that by refusing to accept something as art, you’re criticising it. Jompiy‘s conceptual art. It just happens to be art too. The Stuckist Turner Prize Demo’s anti-art because I could have spent that time painting. Doing this interview’s anti-art.

PUG: I think these are wonderful (looking through the Fembot Oracle cards) ‘Alignment’ look at that one. That one’s beautiful. And this one, ‘Majesty’. Considering these alongside the Stuckist manifesto…

MAD: It’s not just that without Neo, nothing like it would exist. But the drive to make it happen without any real precedent. You can glance and write them off as tarot cards or pretty patterns. He knew that and still put the hours in. There’s the Stuckist manifesto about hiding behind ready made objects and blocking access to inner worlds, then pats itself on the back for taking risks by painting, the safest most lauded and over-rated way of making art in history. I respect artists like Neo who stick to their guns regardless, and as a result create work demanding more than just the cursory glance you’re only likely to get these days. If the Fembots were around 80 years ago the Dadaists would have been all over them, and subsequently a lot more people today. One day the Fembots will get the artistic credit they deserve, but unfortunately not before being officially validated.

The same with Jompiy. I know people will write them off after one glance because there’s no obvious precedent for them. But it’s always the same. You just have to smile, nod and make out like you get and respect what they’re saying. If Cezanne can put up with them, so can I. Just have to remember our audience hasn’t been born yet.

PUG: It’s terrific. They’re very spiritual. (still looking through the Fembot Oracle cards)

MAD: It’s funny how it gravitates us towards each other. Like joining dots. Cosmic forces pulling Ron and Rose from Oswego, you, Billy, me, Charles, a lot of what I just said about Fembots and how rare that is, Luminosity. These things getting drawn into each other’s paths and us into them. Or even if it’s just savvy internetting by people with a lot of spare time, it’s outside the regular channels to those which brings us birds of a feather shuffling into each other’s nests, precariously perched on our siamese iceberg brotherhood nation of solitary nomadic ramshackle explorers, tired of smashing our captive golf balls hopelessly at the distant stars beyond.

PUG: Have the Me a Doll’s got individual titles, like the Fembots?

MAD: They’ve got names. Each is associated with a particular date because I was going to make 366 and do a calendar, which got up to and including February. The Me a Doll’s don’t suggest an inexhaustible number there can be any point in making, like with painting. It might just be that the sixty odd I’ve done so far end up being the lot.

PUG: Do you think you would have started painting if you hadn’t seen Picasso?

MAD: The only reason I started painting was I thought it’d be easy money. I saw an old school friend, Sacha Jafri, on telly apparently making a fortune being an artist. I was working as a Photo Lab Assistant at Boots and playing in 2 out of 3 Rule, resigned to the fact that the band’s never going to pay. Even if we got signed and all that, it didn’t seem the musicians were making much. 28 feels pretty old when you’re in an unsigned band without a regular drummer, and whose singer’s just moved back up to Leeds. There was no back up plan so I guessed I’d work at Boots for as long as people needed their photos developed, which was already drying up. Then I’d have to retrain as something else to finance the music. After that I’d retire early, get a twenty year old’s hair cut for my sixty year old’s face, put on a coffee stained Bowie T-shirt and bore everyone in the pub with stories of how I nearly made it. I had no interest in art or writing and the only paintings I’d done up until this point were the ones I did at school, which showed no promise at all.

So I saw Sacha Jafri on telly. We were in the same year and ‘house’ at Haileybury Junior School in Windsor. You went into one of four houses at Haileybury. Jafri and I were in McCormick-Goodheart (everyone just called it Goodheart), the yellow ties. The green ties were Athlone, the red were Romney and another one I can’t remember but were dark blue. Anyway, how hard can it be? Do a load of sloppy paintings, walk into a central London gallery with a few dry ones under my arm and let the rest take care of itself.

PUG: And then you did your first painting.

MAD: I did my first painting, a man in a turban, and was instantly addicted. At the time I probably couldn’t name you five painters. Picasso, Van Gogh, maybe a couple of others. I didn’t know what I was doing, but this expanse of clear virgin land opened up ahead. It was quit-my-job time, which I eventually got round to four years later. Would have been sooner had I not got married in the meantime.

PUG: And then you started looking more closely at Picasso?

MAD: And the other big names. Eventually got my Mount Rushmore Four whittled down to Picasso, Klee, Cezanne and Miro.

PUG: I like ‘Mount Rushmore Four’.

MAD: Who’s in yours?

PUG: Max Ernst would probably be there, but I tend to look at it as art movements. I’d say Magritte for those two (pointing at her two paintings on the studio wall ‘Halo’ and ‘In Balance’) and have the idea of absence of meaningful government, so I do the opposite to you. I start off with an idea and sort of look for the artists to back up and take it from that.

MAD: What about music?

PUG: I have my favourite bands like the Manics, Ultravox and The Cure but I wouldn’t narrow it down. And then I’ll take a phrase from a song like a bit of poetry and then do a painting from it. Jompiy are quite a lot like Damien Hirst’s spin paintings.

MAD: I liked his figurative paintings that Tate didn’t include any of, in that solo show that had virtually everything else he’d ever done. I think Tate will be showing Heckel’s Horse before long.

PUG: What makes you think that?

MAD: It would be poetic. Darth Vadar comes to his senses and everyone’s rescue. There’ll probably be some new maverick Director that comes along and wants to make an easy name for herself.

PUG: How about a Heckel’s Horse Jr. show there instead? I liked the Heckel’s Horse Jr. book.

MAD: Thanks. They’re currently available to all our Fan Club members on Tiers 2 and 3. If someone was interested in finding out more, all they’d have to do is simply visit https://blackivory.org/fan-club/

PUG: Is there anything planned for Heckel’s Horse?

MAD: As far as I can tell, it’s on the back burner till whoever’s in charge decides the time’s right for a show. Billy’s been trying to push things along for years, pretty much since we started doing them.

PUG: You need this new Tate Director.

MAD: We need someone to forcibly step in with the interest, clout and balls to act irrespective of any commercial consequence or fretting what the art world and its clientele think. Like some benevolent Stuckist ex-hedge fund manager who says “Let’s do a show because of all that stuff in the Stuckism manifesto.” The stuff I like.

PUG: Like a hostile takeover. Might Heckel’s Horse Jr. being published speed things along for Heckel’s Horse?

MAD: Apparently the opposite. It might put them off, but whatever. It shouldn’t be all beholden to any audience thing. There needs to be a punk movement in Contemporary Art. Like Black Ivory but slightly more influential. None of this prissy “We’re not allowed to do this, we’re not allowed to do that. The clients might not like this, the clients might not like that.” I don’t know anything about how the art world functions but there’s an obvious staleness and near-universal obedience to it. Then you get things like Stuckism or our semi-Stuckist-splinter-group Black Ivory that opt out of the “Audience as target” idea and charge head first into disgrace and rejection. Heckel’s Horse is stuck because it isn’t Stuckist.

PUG: It’s not sharing your work with the public. And all those things in the Stuckist manifesto.

MAD: It might be different if they weren’t all six foot tall. Don’t exactly lend themselves to being hung up in the front room. I think they asked the bass player from the Manics what it was like walking around dressed up in band gear, round their local working-class mining village in skirts and makeup, and he says “We just wanted to be hated.” That’s what the world needs. A proper counter-culture punk art gallery that seeks out and exhibits counter-culture punk art irrespective of anything else that has a platform big enough to find the world beyond the artists involved and their friends. A Stuckist gallery but with work reflecting Stuckism.

I like that about Stuckism. I’m not a big punk fan but Stuckism seems to have a lot more punk about it than a lot of stuff calling itself punk. The seemingly repellent and toe-curling bridge-burning stuff Stuckism does. Imagine if some gallery told Charles not to do the Turner Prize demo because of some art world thing they wouldn’t like about it. It’d be a red rag to a bull. Anything of value to be taken from punk’s found in Stuckism. I suppose the last place to look for punk is in all the stuff that looks like it. Who’d think to look into clowns outside Tate?

PUG: I’m sure they’ve already been in touch with Charles.

MAD: When I see photos of Stuckists prancing around in clown costumes it’s appealing because you know what everyone’s going to make of it. Security guards telling us to get a life, hoping the council will come round to sweep us up. Stuckism builds walls between themselves and the people everyone else is so desperate to be approved by. Security guards! But isn’t that what the establishment really want? They all seem to want to be the naughty kid, but only a few have true naughtiness in their blood. Picasso was naughty. Warhol was naughty. Hirst and Emin are pretty naughty, aren’t they? Banksy’s naughty. Caravaggio was naughty. Gauguin was a child-murdering racist paedophile. That’s pretty naughty. Basquiat, naughty. Van Gogh, naughty. Dali, naughty. Michaelangelo, naughty. Pollock, naughty. Modigliani, naughty. Rothko, naughty. Schiele, naughty. Dada, naughty. Stuckism, naughty. Street Art, naughty. Bacon, naughty. Freud, naughty. Kahlo, naughty. Gilbert and George, naughty. Baselitz, naughty. Heckel’s Horse, not naughty.

Galleries want you to be teacher’s pet. Museums want you to be naughty.

PUG: The same for music, writers, poets. What can Black Ivory do to save Contemporary Art?

MAD: We’ll stack a load of Heckel’s Horse Jr. paintings against the walls. A few in the front room with the sofas, tables and chairs and whatnot. I’ll be walking round with a full teapot. Invite some friends round and do it as Stuckism would. Leave the evidence on our YouTube channel as Van Goghian proof for future generations that today’s Contemporary Art wasn’t just the text book crowd.

PUG: Stuckism was quite punk influenced but the art world’s still largely what it was beforehand, and didn’t really respond at the time anyway. Chart music’s now even worse than it was immediately before punk. It seems these radical shake-up’s are all just temporary blips, at best.

MAD: Stuckism bothered though. The rest’s up to them. Like leading a horse to water. Even the anti-establishment are only considered successful when the establishment accept them. The Other Muswell Hill Stuckists should do a manifesto, it’s not our job to be audience. Stuckism‘s not for our benefit, it’s for yours. We don’t need the art world. We don’t need the Turner Prize to show us what a decent painting looks like. I’m only talking about it not shaking up the artworld or not, nothing important, but like we’ve both done loads of Stuckist Turner Prize demos, published a Stuckist Turner Prize manifesto, as far as I know, the Turner Prize is still going strong. So what? Did the demos fail? Are our paintings worse now? If nothing else, it’s nice to get out the house. Usually it’s like, choose a team: brand A or brand B and kid yourself there’s a difference. The establishment’s happy and the hipsters think they’re cool and anti-establishment. Stuckism chooses neither, which I see as the only real anti-establishment.

PUG: A new punk Tate for Heckel’s Horse.

MAD: I did some assistant work for Jimmy Cauty years ago, on these glittery riot shields. I think around 2016. The tracksuit bottoms still have the gold glitter and PVA stuck to them. I can’t remember if I was talking about Heckel’s Horse or something else, but Billy and I couldn’t have done too many by then. It might have been something else, but I tell Jimmy we’ve done all this work and nothing’s getting published, and he says ‘So, when’s the bonfire?’ The man who burned a million pounds. Ten years later, here we are, same situation. Thankfully, as far as I’m aware, still no bonfire. So overall, things are going great for Heckel’s Horse. All the paintings are still probably in existence.

PUG: Just a lot more of them now.

MAD: I’ve got this image of Heckel’s Horse paintings being taken at night to some secret billionaires island off the South Kent coast and chucked on a blazing fire with a load of men in white suits standing round drinking champagne, each with a cigar between their teeth going ‘Ha! Ha! Fuck you Edgeworth!’

PUG: Then there’d just be the Heckel’s Horse Jr. ‘s left and you could sell them for millions.

MAD: You’re a genius.

PUG: All those paintings will end up in a show at some point.

MAD: It’s been eleven years. Could be another twenty, thirty. I had this paranoia, they’d pretend they were by Billy and cut my name out. If Billy and I aren’t around. Even if I’m still around, who’s going to listen to me?

PUG: Do you reckon?

MAD: I don’t even know who it was, but some lying piss-face decided it would be alright to pretend these monoprints Billy and I collaborated on would be better sold off as ‘by Billy Childish’ and not by both of us. So that’s what happened. Like a click of the fingers, “Bye bye Edgeworth.” Pretty unimpressive, I thought.

PUG: Didn’t you say anything?

MAD: No, what’s going to happen? Better to say nothing then moan about it ten years later. It shouldn’t be on me to object if they’re doing it on purpose. It’s like with the Me a Dolls and kids not worrying about who did what. There isn’t a problem when no one lies and you’re up front about the truth. But to be so directed by how they suspect people will react to Billy and I working together. The whole scenario’s a bit of a mess where I think we all come out looking bad.

PUG: I suppose at the end of the day, it’s on them.

MAD: Exactly. You’d think they’d value their reputation more. I’m sure if Billy had collaborated with Tracey Emin on those monoprints, they wouldn’t have decided to find the truth so confusing. But you’ve got to choose your battles, and this one screamed “Not worth it!”. It’s worth knowing how others see you though, and come publication time, the kind of people they really are.

PUG: So it’s not like Damien Hirst and his assistant’s painting butterflies.

MAD: No. Damien Hirst’s different. It’s all declared and everyone knows the deal. There’s nothing dodgy about it. It’s not like some slippery gallerist-type shifts the goalposts after the work’s done, like they’ve got some licence to change the truth. Damien Hirst buyers know what they’re buying. The artists ‘assisting’ Hirst are aware of this from the start. It’s all above board, just like when I was working with Jimmy Cauty as his assistant. There’s no deception. I’m sure when someone buys a work sold as ‘by Billy Childish’, signed only by Billy Childish they expect it to actually be by him. A lot of them, but for a thin prussian blue outline, I did at home in Muswell Hill. So anyone seeing others I did using this quite distinctive thick painterly technique I came up with, will likely assume the ‘by Edgeworth Johnstone’ ones are me copying Billy’s technique. Until I see any by another artist that look similar, as far as I’m concerned, it’s a type of monoprint of my invention which they’ve taken from me, and given the credit to Billy. Not to mention making me look like a copycat when I’m not.

PUG: Didn’t they ask you about it first?

MAD: No, I just get emailed after with some flakey excuse. Apparently they wanted to keep the Heckel’s Horse work special and separate. At the time, I didn’t realise by ‘special’ they meant ‘locked up in a storage container never to be seen again’. If you’re some no-name pushover like me, I guess they think it’s alright. It might all have been a lot more innocent than it looked from my end, but if they’re like this with some few hundred quid monoprints, what’s it going to be like with these crates of 6ft paintings that are worth a fortune? Not exactly reassuring to think of Heckel’s Horse in these people’s hands. They look all professional and high-end from the outside, but behind the scenes, apparently not so.

PUG: Maybe you should have said something at the time?

MAD: But that would be stressful and unpleasant for me, so why should I? I’m not the one with any obligation if I haven’t done anything wrong. And anyway, I can stand up for my work without them. Publishing this conversion, for example. Nowadays, even plebs like me can put the truth on record. Power to the people. I don’t need them to address a problem just because they created it.

It’s also not wanting to flatter them with the idea they’re even worth bothering with. Why engage with problem people when you don’t have to?

PUG: It’s a strange thing to happen. Couldn’t have been very nice.

MAD: I think Margaret Thatcher, a big role model of mine, said “Only take action when you absolutely have to.” And she didn’t take any shit. It’s not like I was upset as much as disillusioned. My friends and I know the truth. The rest of the world can pretend what they want.

PUG: Welcome to the art world.

MAD: A lot of why I started doing Heckel’s Horse Jr. was to get the Heckel’s Horse story out the door. The reason I wanted that so much was because I didn’t want them lying about it later. And apparently there’s a Heckel’s Horse book in production that’s been going on for over a year now, so we’ll see how that pans out. A lot of what we talk about with Heckel’s Horse doesn’t end up happening, but now Heckel’s Horse Jr. ‘s up and running, my gut feeling’s that it’s all time Heckel’s Horse Jr. can make the most of anyway.

PUG: So you should be thanking them.

MAD: I guess so. A lot’s been done already. Billy and I, essentially, want to get Heckel’s Horse paintings in front of people. Billy‘s spoken about it in interviews that I’ve super-glue-referenced into the Billy Childish wikipedia page. L-13 have done a load of prints. Things are going pretty well. The less behind-the-scenes Heckel’s Horse is, the harder I guess it is for the truth to get fudged later. Especially if Billy and I aren’t around by the time anything happens.

PUG: You’ve always got Jompiy.

MAD: Yeah, my solid backup plan. I don’t need to worry about Jompiy getting nicked.

PUG: And the Me a Dolls. How about an exhibition of the Me a Doll’s? Are there physical versions of them?

MAD: No. I’d like to have 3D printed sculpture’s like space suits and the interior would look like a strip club, or like Top of the Pops with the coloured fluorescent lights and dry ice everywhere. I used to have a load of those lights in Black Ivory. We did some music videos with them.

PUG: Are the Me a Doll’s meant to be physical beings? Some of them look very abstract at first.

MAD: They’re creatures you might find in deep space or at the bottom of an ocean. Maybe microscopic. Maybe on another planet. All living amongst each other in a peaceful community. Oblivious to any environment, or form of existence other than their own. Some are clearly predators so can’t be that peaceful. One of them was probably a university brainiac who came up with his own radical, flowery political ideology that sounded great on paper and could be sold to the young majority who didn’t have the life experience or maturity to see through it. They all voted for this nutjob when he realised all he had to do to win the election was get filmed eating organic porridge in a green T-shirt and the whole thing spiralled into a genocidal bloodbath.

PUG: Are you going to do a guidebook to go with the Me a Dolls, like the Fembot Oracle?

MAD: I wrote a book years ago called Shin Detonator. It’s a novel about a mole-like community living under a school playing field. The one at Windsor Boys School before they built an astroturf football pitch over it in the early 90’s. They travel around via these tunnels with threads in them, which sometimes get pulled and raised to the ground causing all sorts of havoc. It’s where the Goat Tap lyrics come from. Thinking of that dank unlit community of creatures humans unknowingly live amongst isn’t too unlike Me a Dolls. I’d like to write a book that, at least starts out, like Shin Detonator about Me a Dolls. As I’m talking now, it’s clear this is going to happen, so yes, there’s going to be an accompanying novel. I doubt it will be a guidebook, but I had no idea what Shin Detonator would turn out to be when I started.

PUG: So it’s not like your book will be guided so much by Neo’s, like the images are.

MAD: I don’t know. It’ll take shape as it goes.

PUG: On that note, thanks Edgeworth.

MAD: Thanks Emma.