Site managed by Black Ivory

Site Map | Instagram | Fan Club

Click HERE for the official Heckel’s Horse Jr. webpage.

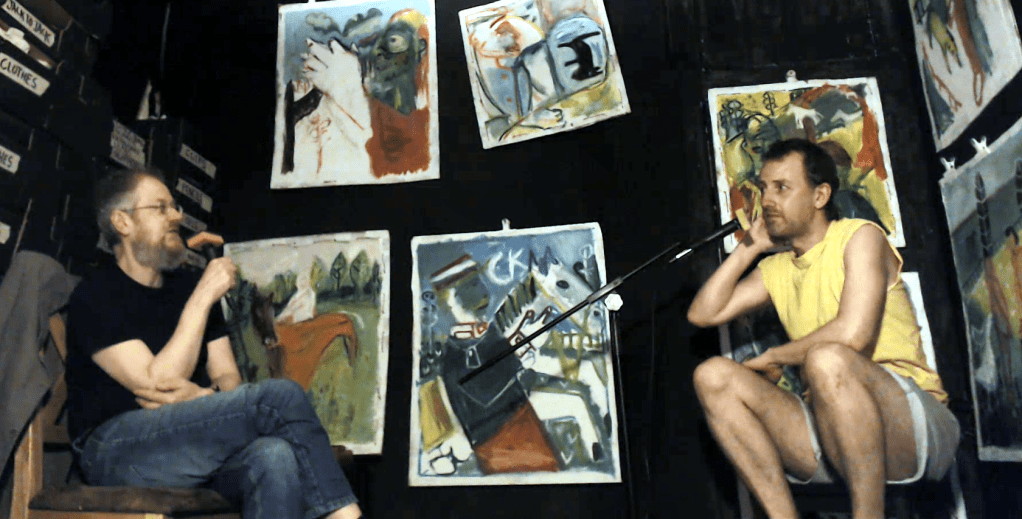

Heckel’s Horse Jr. (aka Edgeworth Johnstone) interviewed by Charles Thomson.

August 9th 2022 at “Heckel’s Horse Jr.” The first exhibition of Heckel’s Horse Jr. paintings, held at Black Ivory Printmaking & Audio Club in Muswell Hill, London.

CT: I’d like to start with your name.

HHJ: For the purposes of this exhibition, my name is Heckel’s Horse Jr., but I’m aka Edgeworth Johnstone.

CT: So, we are here at the exhibition in…is there a name for this galley?

HHJ: Black Ivory Printmaking & Audio Club.

CT: Right, so do you want to say anything about the gallery, the situation, before we get on to the paintings?

HHJ: This room until quite recently, was white. You probably remember it as being painted white. And I decided to paint it black. As I was painting it black, it occurred to me that it took on quite a nice atmosphere. And it reminded me, for some reason of the Stuckist manifesto. So I decided it would be a good idea to host a load of exhibitions here. The first of which was a general Stuckist show…Actually, I don’t know at what point I decided to do multiple shows. I think it was actually after the Stuckist show, I thought I should start doing solo shows. And I’ve got a load of your work, so you were the first solo. And then I thought ‘Well. there’s no limits.’ because it doesn’t cost anything to do. So we can just do as many shows as we like of Stuckism, and it all started off from just painting the walls black.

CT: I must say, I think this is great because people I’ve heard over the years often say ‘Oh, I can’t do a show.’ And I say, ‘Well, you’ve got a flat, haven’t you? You’ve got a house. You’ve got a bedroom. You’ve got a gallery.’ In fact, when I first started out, I did three print shows in America at various galleries in New York and Los Angeles. I knew people and they kindly renamed their living quarters a gallery for a week, and had some of my…So, we’ve got the gallery, which is an example to everybody in the world. Especially people that can’t get a gallery exhibition.

HHJ: You’ll do a better job of it anyway. They say ‘If you want something done properly, do it yourself.’

CT: Did you know my mother?

HHJ: I spoke to your dad once very briefly, but not your mother. It’s funny because your dad thought I was Seb.

CT: That’s my son.

HHJ: Because, for some reason I picked up the phone in your house. I don’t know how it happened. It’s funny the ‘If you want something done properly, do it yourself’ thing because this is my way of showing the Heckel’s Horse work. It’s to just do them myself and then I can show them.

CT: And this segways neatly into Heckel’s Horse. Shall we say who Heckel is to start with?

HHJ: Eric Heckel, one of the German Expressionists, who Billy in particular…I mean, I like Heckel as well, but Billy’s a big fan of his.

CT: Note to the audience: Billy is Billy Childish. Who we’ll come on to in a moment.

HHJ: We started some group a few years ago 2014-15 and I think Billy came up with the name ‘Heckel’s Horse’ for the group. But at the time Billy and I were painting all these paintings together which we called ‘Childish Edgeworth’ because that was us. And then Steve, who works with Billy, came up with the idea of calling our partnership ‘Heckel’s Horse’.

CT: Why horse?

HHJ: I think it refers to a picture that Eric Heckel did that I think Billy’s particularly keen on. To be honest I don’t know. I’m just guessing.

CT: You mentioned German Expressionism. Erich Heckel was a member of Die Brucke group, founded about 1905. Perhaps Ludwig Kirchener was the leading light of it and packed up after 5 years or so from disputes. But there was another German Expressionist group at the beginning of the twentieth century called ‘The Blue Rider’ which people might confuse with Heckel’s Horse. They might think the rider was on Heckel’s Horse but that’s not anything to do with it?

HHJ: No, as far as I’m aware.

CT: I should say for the audience who don’t know, Billy, being Billy Childish, who’s known for various things, particularly his music. He’s been namechecked by quite a lot of famous people including that guy from The White Stripes. Bjork, is it?

HHJ: I don’t know about Bjork, but there are a few.

CT: A number of different people who are quite well known. He’s also an artist. A writer. He’s probably known as Tracy Emin’s ex-boyfriend if the truth be told, which is unfair because he’s got a lot more achievements than that. And actually, that fact that she once said to him ‘Your paintings are “stuck, stuck, stuck” because he was painting and she exhibited her bed…or she hadn’t done it by then but the sort of thing she was into. And he wrote that in a poem and in 1999 he read the poem to me and I said we should call ourselves ‘Stuckists’, and then the Stuckists art group was founded to promote figurative painting. That was 1999. You’ve founded a Stuckist group. There’s about 250 Stuckist groups in 50 countries around the world.

Steve is the guy who runs the L-13 gallery near Clerkenwell/ Farringdon area of London. And the L-13 was named after a German Zeppelin bomber which destroyed some property in that area. I think the gallery was next door to the destroyed property. Anyway, that’s where L-13 comes from but it’s moved from that place. And they work together. Steve, at L-13 promotes Billy’s work. He also does stuff himself, doesn’t he?

HHJ: Harry Adams.

CT: There’s also Jimmy Cauty of the K Foundation. Burned a million pounds. Jamie Reid who did the Sex Pistols ‘Never Mind the Bollocks’ album. So that’s all the background that I didn’t really want to say, but anyway you got to know them. And you go down every Monday and work with Billy in his gallery. Billy’s gallery is a very large room that is in Chatham Dockyard.

HHJ: His studio, we’re talking about.

CT: Yes, I said ‘gallery’ did I? That’s his studio. You work there. Billy does very large paintings.

HHJ: Huddie Hamper as well. He’s there every week.

CT: That’s Billy’s son. Billy does 8ft/ 10ft paintings in a couple of hours.

HHJ: Maybe not two but in an afternoon he’ll do a huge painting from start to finish.

CT: But the ones he does are a very different style. One could say he’s become quite academic. They’re drawn accurately, in terms of perspective and anatomy and so on. And they sell very well in galleries in Germany and New York but alongside those paintings there is another activity going on which he does with you. Would you like to tell us how that activity started and how it happens when you’re there together.

HHJ: Shall I start from the point where I was already in his gallery painting? Or I can start from where I first got in touch with him.

CT: Well start from the beginning.

HHJ: Now I’ve got to try and remember how it happened.

CT: Well you went to L-13 the gallery and saw his shows and talked to him, I presume.

HHJ: Maybe a couple of words. Until he emailed me out the blue one day I’d said hardly anything to him. I’d met him a couple of times at L-13 but…he just emailed me. I think you said to me that you speak to him on the phone every now and then, to Billy, and you mentioned me. I guess he heard of me, probably, through you. I don’t know.

CT: I should say I’ve known Billy since 1979. We were in a group called The Medway Poets. Tracey Emin was a young fashion student and was going out with Billy. So yeah, we had had our ups and downs, but we’ve gotten on reasonably well for the last twenty years or so.

HHJ: So I guess he probably heard of me through you and then he emailed me, and I ended up talking to him through email having not really ever spoken to him before. Only small talk at an exhibition and he said ‘You should come down one day.’ That was it. He wanted to see my paintings because I was showing him my work and he said ‘Oh, you should bring them down one day.’ So I did and he saw them and we had a chat and then he said ‘Is it quite a bother for you coming down here?’ he said one day. and I said ‘It’s quite easy.’ because I had a car at the time. I said ‘I can drive to Chatham in three quarters of an hour.’ And he goes ‘Well, you should come down the studio one day.’ So I went down the studio and I was working and he says ‘You know what you should do. You should get some big canvases’ because he thought it would be better for my work and this is funny because Billy didn’t know me and he just offered. It’s very kind of charitable. So he’s helping me out a ton and he says ‘You should get a load of canvases and we’ll put you up in my studio and I’ll give you a load of space because I think if you work bigger it’ll work. It will be better for your style of painting or whatever, because I was always working small because of my living situation. So I did that, but I think, before I got the canvases I turned up with a load of cardboard and I was doing a painting on cardboard that was a copy of a block print I’d done. It was a portrait of Picasso and it had a couple of birds on it. Sort of pecking his eyes out and stuff like that and he goes ‘Oh that’s alright but..’ he said ‘Can I…’. Did he ask? I don’t know. I think he probably did. He said ‘Wouldn’t it be good if it had a couple of lines.’ So I had three or four of these Picasso’s. They weren’t particularly precious or anything. They were on cardboard and he painted some eyes or a few white lines on them and it looked a lot better. And he goes ‘Ok, well that’s quite good.’ so then I start painting on these great big canvases. Like six foot canvases. And again, the same thing happened because it was very much kind of…Billy was kind of helping me sort of getting into a different area of painting so he would paint on them and the first one we did on canvas, that looked really good as well. So he goes ‘You know what, we should do a ton of…’ Well, he didn’t say to do a ton, but ‘We should do more of these.’ and we ended up just continually doing more and more and more because they’re so easy. They’re easy for me because I can just start and I don’t even have to bother making them look good. I just need to leave them in a good state for Billy. So I painted and he would come over and he’d do…and it was just so automatic and so sort of natural and they had a kind of look to them that neither mine nor his works do. They’re their own thing and it kind of snowballed and ten years, or nine years later, we’re still…to be honest since covid we’ve only done a couple. We’ve slowed right down recently.

CT: How many do you think you’ve done all together?

HHJ: I reckon between 150 and 200.

CT: So you usually do one each visit, do you?

HHJ: Not anymore. No.

CT: When you were working before, at your peak.

HHJ: At our peak probably one a week. Probably averaged one a week.

CT: And you exhibited these at Pushkin House. What is Pushkin House and where is that?

HHJ: That was a group show. Pushkin House is in central London and is some centre for Russian culture. I don’t know exactly what their description is.

CT: Good job it’s not called Putin House. Anyway, sorry.

HHJ: I don’t know how that show came up because Billy and Steve tend to do the organising side of things and I hear about it later.

CT: I just want to make the point that you have shown them there.

HHJ: We’ve been in three group shows. One was Pushkin House. That was the most prestigious of the three. We did one at Sun Pier House.

CT: That’s Chatham in Kent, near Billy’s studio.

HHJ: And there was some show in Russia where they showed some Heckel’s Horse. Although I don’t think we were called ‘Heckel’s Horse’ at that point but some of them were showed over there. I don’t know. All I know about that…I looked on YouTube one day and saw my paintings being auctioned off, and no one told me they were selling them.

CT: This is the joint paintings was it?

HHJ: No, these were oil transfer drawings I did. I just saw on YouTube that my paintings were being sold, which was interesting.

CT: So far so good. Now these are not actually Heckel’s Horse paintings.

HHJ: No they’re not.

CT: They are your copies of…Oh, shall I, before I forget, are these Heckel’s Horse paintings for sale or are you keeping them privately?

HHJ: Keeping them. I’ve only done eight and I don’t really want to sell them.

CT: No, not these. I’m talking about the ones you did with Billy.

HHJ: I don’t know.

CT: Just for the viewers. We have a few millionaires knocking around.

HHJ: They’re not sort of…you can’t buy them online or anything and there’s no gallery showing them. But if someone was to ask I guess everything has a price.

CT: This is very amateur, by the way. Just in case anyone here thinks this is a professional job with a whole camera crew, sound recording, overhead lighting and so on and a van outside with masses of wires trailing out of it, it’s not. It’s just one camera on a tripod. Actually, they’ve probably guessed that by now anyway.

HHJ: I don’t think we were fooling anyone.

CT: We could pretend it’s a high end thing meant to look like a low end thing. Just to do a quick detour before we get onto the paintings, a detour about the video here. This is a homemade show. What about your videos? What’s the philosophy of the videos? How do you do those?

HHJ: Just film them. Put them on YouTube. Put them on social media. We’ve got an audience of like four people.

CT: So it’s quadrupled since I last looked. That’s bloody good. You’ve gone up 400%.

HHJ: It’s kind of in keeping with the whole atmosphere of what we’re doing.

CT: Billy once told me that he did a gig in Germany and ten people turned up. They said ‘Look, we don’t expect you to play because you don’t have a proper audience.’ He said ‘You’re here. You’re the audience. We’re playing.’ And it turns out that one of them was an influential music journalist.

HHJ: Yeah, you never know.

CT: Well does it matter? What’s the difference between having an audience of one and having an audience of ten thousand or a million?

HHJ: Exactly.

CT: I mean, if you add noughts on the end. My experience of curating shows is that I do it because I enjoy seeing the paintings. Which is probably a selfish approach but means I don’t get het up and frustrated about who’s coming through the door and who isn’t. You know, if the people who are there enjoy it. Those four people really get something from it. You don’t know how it’s going to affect their lives and things tend to pick up later. When Cubism started there were only two people who knew about it. Picasso and Braques. Just two people. It’s grown a bit since then.

HHJ: You never know.

CT: So everything is homemade.

HHJ: Yes.

CT: Now, as I said, these are not Heckel’s Horse paintings. These are fake Heckel’s Horse paintings. Not fake perhaps. That’s not the right word. You have made your own copies of Heckel’s Horse paintings. These are your copies of the work you did with Billy. These are on cardboard. The ones you do with Billy are on canvas aren’t they?

HHJ: Linen, but yeah. Stretched Belgian linen. Well no, actually some of them are on canvas but most of them aren’t.

CT: For the viewers who don’t know the difference, it’s all the same. It just looks like a canvas, stretched. One is made from cotton and the other’s made from linen. But it don’t make any bloody difference does it really? Except for linen lasts longer than canvas. But the sails from Nelson’s Victory lasted quite a long time. They’re still there with lots of cannonball holes in them and stuff. They found them the other day. A couple of years. Or three years ago or so. Anyway, they’ve survived. Are the originals bigger?

HHJ: Yes, they are.

CT: How much bigger? Let’s take this one for example.

HHJ: That one’s a 6ft by 5 I think.

CT: This one’s about 40 x 30 or something and it’s your reproduction of a 6 by 5ft. So, quite a lot bigger. It’s like what, a quarter of the size? Why did you decide to do it this size?

HHJ: Just that’s what the materials are that I have. I didn’t need them to be big.

CT: Why did you do them?

HHJ: Lots of reasons. I suppose the one main thing is I like them and I can do them. It’s not that I could….I definitely couldn’t do them without Billy, but I am sort of quite…

CT: No, sorry, why did you do these?

HHJ: Sorry, I’m not trying to say I couldn’t do the main Heckel’s Horse without Billy, when I say I’m quite interested to see what they look like when I just do them on my own. You know what I mean?

But also, I wanted to use this space to do the show. Some sort of thing for Heckel’s Horse because Heckel’s Horse…despite Billy and I always wanting to do a show, it’s never really been possible and I thought ‘Well, I’ve got Charles’s show up here.’ Which I did at the time.

CT: That’s me by the way.

HHJ: And the plan was, I think, for Jasmine to go next.

CT: Jasmine Surreal. Yes, her paintings are down here actually. Next to me.

HHJ: Jasmine Surreal was lined up next but I thought ‘I could take Charles’s work down now and get mine in quickly because I’ve got you, Ron Throop, Emma Pugmire, and I was thinking, ‘When am I going to do my show?’ because I want to get mine done. So I thought if I quickly took down yours I could do an Edgeworth Johnstone show. But then I thought ‘I’ve got no enthusiasm for doing an Edgeworth Johnstone show but what I would like to do is put up Heckel’s Horse paintings.’ But, obviously I can’t do that because they’re not mine. They’re me and Billy. So I thought ‘If I do them myself then I’ve got complete control and I can put them up.’ And I can not only do an art show but I can promote Heckel’s Horse, so more people learn about Heckel’s Horse and also for the artistic value in themselves. Hopefully do some decent paintings.

CT: So what’s this exhibition called? Who is it by?

HHJ: It’s called Heckel’s Horse Jr. and it’s by Heckel’s Horse Jr. A self-titled exhibition.

CT: Ok, so, let’s just take this painting. I’m familiar with some of the originals so I recognise these are the types of paintings you’ve been doing. The ones I’ve seen in Pushkin House, for example. But I don’t know them in intimate detail so could be fooled because they’re kind of like it. So if I put the original next to this, apart from the size what differences will I see?

HHJ: Not much. I have pretty much just copied them. This one, we did after a painting by Mikhail Larionov. We did quite a lot after Larionov who is a Russian painter from a couple of hundred years ago.

CT: Early twentieth century.

HHJ: Most people might know his…I don’t know if they ever got married, but his partner Natalia Gonchorova is quite well known.

CT: Yes, is the highest selling female artist at auction, I think.

HHJ: He was Russian but there’s links with him and Picasso and that whole avant-garde crowd. Billy and I did a load of paintings after Larionov and this is painted after the first Heckel’s Horse painting we did of a Larionov painting.

CT: Have you more of less copied a Larionov painting?

HHJ: No.

CT: Is it in the style of, or inspired by?

HHJ: Inspired by Larionov. So the Heckel’s Horse paintings that were done after Larionov are not copies. We use Larionov as a starting point but the end result looks quite a lot different.

CT: I see, so the whole Heckel’s Horse project stem from Larionov’s inspiration?

HHJ: No we were already painting together before we started doing Larionov paintings.

CT: In the same style?

HHJ: Pretty much. I mean, we were already…

CT: So he just got hijacked and incorporated into it en route, and you moved on. Like a little bump in the road, and you carried on going?

HHJ: We didn’t stop, you know what I mean? We did them as well as. It’s like, instead of always doing a painting from, maybe a sketch or even just off the cuff, occasionally Billy would have this Larionov book and we’d go through it. We’d pick out paintings that we liked. But it’s not like we stopped doing Heckel’s Horse and we started doing something else. It wasn’t like a chunk of work in its own right. We just happened to do lots of Larionovs.

CT: Yeah, but it’s not called ‘Larionov’s Lunger’ is it? It’s called Heckel’s Horse, so…Have you done the same thing with Erich Heckel’s work? Your own variants of that?

HHJ: I think we have. I think we’ve done maybe two or three. More Larionov’s than anyone else but we have done a couple of Heckel’s as well.

CT: It seems really that these people are just a catalyst for you to do your own work.

HHJ: Yeah.

CT: So if we get on to the paintings themselves. The first thing that you would notice about them is there is a figurative element. There’s often a person or people. Sometimes a horse. There’s a horse and person there. There seems to be a person in all the ones that are here. Is there a meaning? A narrative? A story? Or is it just a visual? Is it just that it works visually. Like you have a dream and you see things going on. Or are you thinking actually ‘This is a particular soldier.’ Maybe it’s Larionov in uniform, or something like that. Or maybe ‘He painted these Russian soldiers so we’re going to comment on that.’ Or maybe Kirchner of the Die Brucke Expressionist group was a soldier for a time. Does that come into it? Or is this me just projecting onto it things that I know. Am I meant to be doing this? Or is there a story that I should know, that you know. Or is it just a guy on a horse with a bit of a uniform?

HHJ: As far as I’m concerned, there’s no real comment or meaning or requirement to know anything. They’re stand alone paintings that you don’t need to have any background knowledge to appreciate.

CT: Do you have any? Do you think ‘Ah yeah, this is reminding me of …’

HHJ: No. All I’m trying to do when I’m painting is do a good painting. There’s nothing else.

CT: Ok, well I’m going to challenge you a little bit on that because he is in uniform. It’s like a military uniform. Not like a contemporary, modern day soldier. Unless he’s dressed up in traditional uniform so you must have got that reference from somewhere. It’s not an accident. You can’t just do someone in a uniform without knowing that people wore uniforms.

HHJ: Well I’m just copying the painting.

CT: No, I’m talking about the original painting.

HHJ: What, the Larionov? It’s a painting of a Heckel’s Horse painting which was based on a Larionov.

CT: That’s what I’m getting at.

HHJ: And in the Larionov painting, that’s what the guy’s wearing.

CT: Yeah, so he knew he was painting a cavalryman.

HHJ: Larionov would have done, yeah.

CT: He definitely knew he was painting a particular soldier at that time in history. I presume it was just before the First World War.

HHJ: I don’t know.

CT: So he knew what he was doing but you’re not really bothered with that side of it at all.

HHJ: Not really. No. I mean, not at all. I like a painting to be a good painting. I don’t really mind the background story.

CT: One of the things that’s said about figurative painting is that every figurative painting is an abstract painting. And you’re demonstrating that.

CT and HHJ are now holding one of the paintings from the show upside down in front of the camera.

CT: The reason I’ve done that…Kandinsky….well, he was doing these figurative paintings and he came in one day, and he saw this painting propped up with the most amazing colours. Completely abstract. And then he realised, it was one of his figurative paintings, of a landscape or something but that gave him the idea that he could just paint abstract without having to have a figurative work. A figurative image. And when you look at things in different ways. Like, shall we try it sideways as well? I mean, it works without even having to know there’s an image. Rather like Chinese calligraphy type paintings, where someone will do beautiful brush marks all over the surface and it’s that movement, that gesture that the brush makes which gives it the interest. And anybody that’s done something like that will know that you can do that brush mark and it can be very dull and prosaic, or you can do it and the variation, the pressure, and the dynamic and the direction it’s going in, the flow of the ink and so on comes alive. So I think it’s not just a question of painting the subject. It’s really how you paint it. I think, how you paint it comes from who you are. And I’ve thought about this quite a lot, before you have any art you have an artist and they’re going to leave their stamp on the painting. They can’t help it. If someone is a superficial person, they’re not suddenly going to find an amazing depth when they do a painting. If they do then they’re touching a deeper part of themselves anyway. But if they never access that deeper part of themselves, and unless it does come out despite themselves, if you like, their work’s going to be superficial. So every mark. Every colour. Every decision…I mean, conceptual art has very few decisions. Damien Hirst’s shark has one decision. I will get a shark and I will put it in formaldehyde. That’s the decision. Whereas take any of these paintings. Every square inch has got a different decision in it. There’s a red here that is slightly different to the red there. This band is a similar colour to that mark. That’s almost a rectangle of paint. This is a rectangle. A bit of a wonky one, but it’s a different kind of rectangle. I know I’m going on a bit here. You mentioned Jasmine Surreal. I did a big painting once. It was a ten foot painting. I’ve only done one that size. I wanted to get it out the living room but it’s got agitated brush marks all over it. Different colours. Different intensities. And she looked at it and she said ‘Are you feeling more passionate, or anger there? And then you were feeling quiet…’ I said ‘You’re right.’ You could read the marks and the colours as if they were words and basically they are. We’re talking about language. It’s not one that our society, our culture is particularly skilled at reading. You know? We’re taught to read words but people are generally not taught to read images. Obviously sometimes they do it instinctively and they look at something and say ‘Oh, that’s good isn’t it.’ They’ve read the colour and the shape. Or they might say ‘That’s a bit bright.’ You know? The intensity is blinding. So there’s a primitive reading but not a very subtle and sophisticated one. And it’s like wine. You start out with a bad sweet wine and ten years later you turn your nose up at it because you’ve developed a palette. It’s like anything. The more you do it. Using words, for example. You don’t expect a five year old to have the expressive capability of Shakespear. It’s something you develop and become more sophisticated, more sensitive to, hopefully. If it’s going in the right direction. So what I’m saying is, in these paintings, there is a display of a lot of what I’m talking about. The feeling for the right colour, the right shape and the right place.

Now to my mind, there’s a balance between what you’re painting and how you’re painting it. In abstract work obviously, it’s completely how you’re doing it because you’re not painting any specific subject and I think the interesting thing about figurative work is that tension between what it’s showing and how it’s showing it. Do you have any response to all of that?

HHJ: I don’t think people who look at paintings are aware of how much you’re considering as you’re doing them. Especially in my work that can look quite sloppy and I’m sure I’m talking for millions of other painters who…There’s a very deliberate move in everything you’re doing that’s totally beyond the concept. I know you started from saying Damien Hirst’s conceptual work was ‘Oh, it’s a concept.’ Well, who cares about the concept? You can start off with that, alright fine, but what I like in art all comes from that point onwards. And just that satisfaction you get from seeing things that look kind of balanced and correct in an abstract sense but it would have to be attached to something figurative for it to have any kind of hold on me. I couldn’t care less about abstract work at all. It has to relate to something in physical existence otherwise it just goes over my head, and I think there’s a balance there. I’m trying to do as much abstract work as I can in a figurative painting and having nothing else at all. Not having any concept, or meaning, or narrative. If you take all that stuff out you’re left with a more pure thing at the end of it.

CT: As soon as you do anything figurative you’ve got a narrative, whether you want it or not.

HHJ: I’m just trying to do stuff that just looks good. There’s not really any kind of emotion in it or need to express myself.

CT: At the end of the day, I particularly apply this to poetry, which I write a lot, which I’m doing at the moment. At the end of the day, what’s left is the poem and someone reads that, and that’s got to work. The poem has got to work. So I might write about my life in the poem and it might be something that’s particular to my life but it doesn’t sit in the poem because when you’re creating something I think there’s a dialogue between you and the thing you’re creating. It’s telling you what to do. This has happened to me quite a lot. With painting, for example, I’ve thought ‘Right, I’ve got a red there.’ I’m just speaking in general terms. Crude terms. ‘A red there. A green there. And I’ll put a nice yellow there.’ So I put the red there, and as soon as I’ve done that I realise the green’s not going to work and the painting’s saying ‘Hang on. This is your bright idea but look at it. It’s not going to work is it? Actually you need the yellow there.’ And then maybe, oh we need a blue up there and then later on the colour that I left out pops up down here, so it’s not lost. It comes up again quite often in a different form, so there’s that interaction. At the end of the day you’re creating something. You’re making something and if you’re sharing it, I think you have to consider who’s looking at it. Whether you do that consciously or unconsciously. Otherwise, what’s the point of showing it? If you’re not creating something that someone can look at and get something from, there’s no point in showing them.

HJJ: I feel like I don’t even have a choice when I’m painting. It’s almost like, it needs to be that and can’t be anything else, so I can’t even consider ‘If someone else sees it they won’t like it, so I need to try and do this, or try…I’m really at the mercy of what feels like the right thing to do.

CT: I think we’re actually saying the same thing. I’m not saying you should adjust everything because someone’s going to look at it. Because actually, that happens to me. I sometimes have an idea and I think ‘I could do this painting and it’s just too easy. It’s just too simple. People are going to think it’s rubbish. I don’t want to do it but I really want to do it. People are going to think it’s rubbish.’ So I just do it and then they come along and say they really like it, but that’s just me because I suppose I have a sort of awareness to what’s going on outside me.

HJJ: You’re doing what feels like the right thing to do anyway.

CT: Yeah, but sometimes there’s a block. Less so nowadays I must say, but in the past more so. You don’t have that. But you talked about doing what’s right on the canvas, and that’s exactly what I’m saying, that it’s telling you something.

HJJ: I was thinking this two days ago: I was doing a painting of a fish under a boat. I realised that I don’t have any choice. This is going to be a fish under a boat. I know if I come in with my bright idea it’s going to screw it up. You’re just following orders really.

CT: The one that we pulled down from the wall and showed in front of the camera. I’m facing that so it’s the one that’s easiest for me to look at. There’s a man that seems to be wearing a hat and there’s an animal of some kind. Is it a pig of some kind?

HJJ: I think it’s a dog.

CT: But I get a feeling from it. It’s not unpleasant. I think just a few lines can be very suggestive. The man’s face. There seems to be a certain thoughtful quality to it. He seems to have stopped and be thinking about something. That’s something everyone can relate to. And the animals there. Again, you can relate to that. It seems to be absorbed in its own life. Mooching around the ground. Sniffing the ground. The man seems aware of it but not really relevant to him at that point in time. And he’s in front of a building. Looks like his house. So you’d think it’s probably his home and maybe it’s his garden. That sort of thing. You get a feeling for the whole thing but that could be done in a very illustrative way. In a kind of Norman Rockwell or something, and you wouldn’t get the same feeling from it though. You wouldn’t get the same atmosphere and the whole sketchy thing suggests a liveliness. Conveys a liveliness. A sort of spontaneity which makes it living, whereas a Rockwell is a very skilled illustration but it’s kind of frozen in time.

HJJ: It’s as different to what I’m doing as making cheese or playing football. I know that technically, they are both called paintings, but other than that there’s nothing. I think there’s a lot of…art’s such an overriding term but so’s figurative painting. There’s figurative painters that are not doing what I’m doing at all and that’s not necessarily a good or bad thing. Even within Stuckism. There’s painters like Jonathon Coudrille, for example. He’s absolutely brilliant at what he does but me and him, for example, I don’t know what’s going on inside his head, but I just see it as completely different.

CT: But you have been exhibited, more or less, side by side.

HJJ: Yeah.

CT: Stuckism, the art group mentioned earlier, which I had the idea of and founded with Billy Childish to promote figurative painting. But my idea of it, from the outset, was a very big umbrella. So you’d have very expressionist work. Very highly polished work. Cubism. Pop Art. Figurative Pop Art. Realist art. All different kinds of styles. It wasn’t a stylistic thing. What was important was that the artist had a strong sense of authenticity. Of honesty to themselves of their experience of life and have the skill to communicate that in their own style. And really Modernism is the history of people inventing their own rules and their own styles. Van Gogh invented his own rules, which was that things could be wonky and distorted and would be painted in a very agitated, and often swirling brush marks to express all the energy he felt in the universe. Whereas another artist, obviously Picasso for example, chose to fracture things. He didn’t, in his Cubist period have the same…well he had some of the same brush marks, but not the same effect at all. It was more or less fractured plains. He was interested in a sort of…dissecting something and putting it back together again. But it worked in his terms. If you look at any of the Modernist artists whose work is successful, they’ve invented their own domain to work in. That’s Modernism, then we come on to Postmodernism where people plunder it. Or Remodernism, where we value it and try to develop it.

HJJ: Any good art is authentic. Van Gogh said ‘Anything done in love is done well.’ I read the Stuckist manifesto and I think ‘That’s how I write songs.’ Whenever I’m doing anything, it’s just that feeling of authenticity and nothing else. Then what you’ve got will be original because despite the fact that there’s eight billion of us, we’ve all got individual handwriting. It will be original by default. You don’t have to try and come up with some clever idea to separate yourself from the crowd, which is what I suspect is going on in a lot of contemporary art, and the art at the time of the Stuckist manifesto. It’s a contrived originality. When I look at Van Gogh’s work, I don’t see someone who’s struggling for an idea, or came up with something. I just see someone who’s doing what he feels he has to do, and by default happens to have just made something that’s original. So going back to what I said about Jonathon Coudrille, maybe I was completely wrong. Maybe we’re essentially the same thing, just manifested very differently. Essentially it’s just two artists doing their stuff and there’s no other way it can be done or said.

CT: I used to do a lot of teaching poetry at schools, freelance. I went round schools and performed and so on. I told the children in the class, I said, I want you to write about the thing you’re a world expert on. ‘I’m not world expert.’ I said ‘Yes you are. What did you have for breakfast this morning? What did your dad say? What did your mum say?’ Oh, this, that and the other. ‘Well, you’re the only person in the world that knows all that aren’t you? What was it like when you went to school? What did you see? Who did you talk to? How did you get here? You’re a world expert on that.’ And then they start trotting out ‘Oh yeah’ and this happened, and that happened, and suddenly you’ve got this whole treasure trove of personal experience. Or you could say to someone ‘What was the worst thing that happened to you? What was the best thing that happened to you?’ They come up with these extraordinary things and it’s all there in, so called, everyday life.

I totally agree with you about this striving in art for, so called, originality. What it comes down to is, trying to find a material that hasn’t been used for art and calling it art. So you find a shark that hasn’t been done in art, so you call it art. ‘Oh, that’s original.’ You exhibit a bed, like Tracey Emin exhibited her bed. ‘Oh, no one’s done that before.’ They had actually, but never mind. ‘Oh, you’ve made a sculpture out of bread.’ You make a sculpture of your head out of your own blood and freeze it. ‘Oh, that’s new isn’t it. That’s new.’ Well, what’s the difference between the sculpture of a head in blood in a freezer, and a sculpture in bronze? It’s got the same contours. It communicates…’Oh, it’s a concept.’ But it’s not actually a very interesting concept. Ok, you get it. You get the joke, or the cleverness being ‘Oh, that’s clever.’. And then once you’ve got it, it’s ‘Oh, it’s just a sculpture,’

HJJ: You could spend all night just coming up with arbitrary stuff like that, that has no depth to it and is new. I’m sure no one’s stuck an ironing board on top of a carrot and spun it on the head of a daisy. Is that a genius idea because it’s new?

CT: It is now.

HJJ: We could come up with a list of 500 by tomorrow morning and it’s all just complete nonsense.

CT: Of course, you’ve taken part in Stuckist demonstrations against the Turner Prize outside Tate Britain for several years, and that’s been going on for about twenty years. It’s stopped now because I got fed up with it. I was actually given a conceptual art award by the Proto-mu group for the demonstration against the Turner Prize. And, of course, if we said it was a conceptual art piece you would have been treated very differently. My hope was always that it would be nominated for the Turner Prize. So our demonstration against the Turner Prize would be in the Turner Prize as one of the nominees and simultaneously we could be outside doing a demo.

HJJ: We’d have to be.

CT: Against our demo that was in there.

HJJ: I think I made a quick video today and said that that’s the best nomination I’ve heard.

CT: Is there any more that we should say about this? Just….how does this relate to your other work? Does your work with Billy relate to your other work? I have actually referred to Billy’s other work but perhaps you could say how it relates to his other work.

HJJ: These, pretty much, felt to me like doing my normal work, even though I was copying the Heckel’s Horse paintings. The Heckel’s Horse paintings are completely different to my work because I’m not in complete control. If I’m not in complete control, even if I really like the work, in a way, I almost really don’t care. I’m not being derogatory to the Heckel’s Horse, but when I’m painting them I can do whatever I want and leave it to Billy to sort the problems out.

CT: Perhaps his other work, which goes in galleries, is more demanding in some way. Discipline and control, because it is very controlled work.

HJJ: I don’t know. The Heckel’s Horse one’s are a discipline and a control in a different manifestation. It’s one of those things where, even though they look very loose, if one brush stroke is wrong we’ll change it.

CT: But it’s the difference between someone doing accounts, where every figure has to be precise, and it’s like again, and again, and again. And the discipline of going down a ski slope.

HJJ: I don’t know how Billy feels when he’s doing his own painting. Sometimes things can appear that they must be that way, but the experience of doing them…

CT: I wasn’t saying Billy’s was like doing accounts. I was just drawing a distinction between how you can have a distinction between different types of discipline. Obviously, going down a ski slope very fast, you need discipline, but it’s a different kind of discipline. All I was saying is that there’s different kinds of discipline. Going down a ski slope is, presumably for most people, more enjoyable. Not everybody. Paul Harvey does incredibly detailed, meticulous work, would drive me bonkers and he enjoys it. He thrives on it. It’s him to do that. He finds it very therapeutic. Very fulfilling. I’ve done, when I was at Foundation, I taught myself to do quite meticulous observational drawing and paintings. A lot of it was mechanical. And then I ended up thinking, why bother when you can take a photograph? I say that a painting is like a photograph of the inner world, and a phonograph is a painting of the outer world. Because you can’t take a photograph like any of these.

HJJ: No, but, like I say, there are people out there that probably find my work…doing that mind numbing…but when you asked about relating it to Billy’s work, I don’t really know. You would really have to ask him.

CT: No, I’m more interested in how it relates to your work because you’re here. I just thought there might be a little gem here about Billy and…what has he said about you doing this work?

HJJ: I only done these a few days ago. Actually, I did see him Monday…

CT: No not this. All your work together.

HJJ: What, about my work in general?

CT: No, no, your collaboration. What’s he said about the work you do between you?

HJJ: I think both of us are really…I think we both said these are our favourite paintings of any paintings. Which sounds quite big headed to say, but it’s the truth.

CT: If Picasso said he’d done something original, that’s fairly accurate. I mean, is that big headed? That’s ludicrous. If he’s said ‘Oh, it’s nothing. It’s not going to have any effect on the world at all.’ That would be a load of rubbish.

HJJ: Exactly, you can either tell the truth or not. If it comes across as big headed then that’s too bad.

CT: I don’t think so.

HJJ: It shouldn’t come across as big headed because you don’t have a choice. If you think that, you think that. I think Billy and I both rate the Heckel’s Horse paintings extremely highly, otherwise we wouldn’t have done two hundred of them. We wouldn’t have bothered.

CT: You said that you start them. You bash something down. Excuse the word ‘bash’, but you create something. You put down what you feel like. Marks, presumably you’ve suggested there’s a dog, or a figure and a house, or whatever, or maybe not all of those things, but some of those things. It’s not just abstract marks.

HJJ: No, I don’t do abstract. I always paint figurative. I never paint abstract.

CT: So you’ve got some kind of figurative image there.

HJJ: Always. Yeah.

CT: And you said he comes along and works on it, and pulls it together.

HJJ: Usually that’s how it happens.

CT: But does it happen the other way round? Or do you then ever work on what he’s worked on?

HJJ: Yeah, I do. Most of the time…

CT: And then does he ever work on what you’ve worked on? How many times could that happen?

HJJ: There’s one painting we did of a bullfighter with a bull on top of him, and we went back and forth at least five times. We ended up painting the same painting at the same time. I think we were both at a loss and then we turned it round, we kind of went all over the place. I don’t think there’s been another painting like that one.

CT: Did it work out in the end?

HJJ: It always does. That’s the good thing. Like with my paintings as well.

CT: But did you have favourite bits of the painting and then he comes along and obscures it? Does that happen?

HJJ: No, because I don’t…

CT: Or vice versa? Does he sometimes get a bit disgruntled? ‘Oh that was a good mark there, and you decided you’d paint over it.’?

HJJ: Not that he’s told me.

CT: So it requires a lot of tolerance on both sides.

HJJ: Well, I don’t care anyway. I’ve never done a painting with Billy and thought ‘I hope he doesn’t touch that bit.’ because the thing is, whether it’s good or not is all relative to what’s around it anyway. So a good thing there is only good if everything around it…so you know it’s all going to change anyway, so I don’t really care what he does. And anything I do, if I really liked it, I could just try and do it in my individual work

CT: I think we’re probably getting towards the end of the conversation. Does it feel like that? Normally at the end I think people say ‘How do you see it going?’ Where’s the future?’

HJJ: For Heckel’s Horse Jr. I think I’m going to carry on doing more because these were so easy and I like the results. Heckel’s Horse? I don’t know because we’ve kind of stopped. We haven’t really done any in..I mean, we’re talking in August 2022…

CT: But you go down there still?

HJJ: I still go down there, but we’ve stopped doing Heckel’s Horse paintings.

CT: What do you do when you go down there?

HJJ: I just do my own work.

CT: Oh, I see.Why?

HJJ: We just haven’t been doing them.

CT: So do you think Heckel’s Horse has reached its end? Or do you just think it needs a break and you’ll get back to it again?

HJJ: I really don’t know. I mean…

CT: Watch this space!

HJJ: It’s been so long. It’s August 2022. Covid was what? 2020?

CT: Let’s end by blaming Covid.

HJJ: It’s Covid’s fault and Billy and I will get back on it asap.

Join the Fan Club to receive our regular publications

(Free worldwide shipping included).

Watch our Weekly Instagram Live Video Podcast: Thursday nights at 7pm GMT.

Site managed by Black Ivory

Site Map | Instagram | Fan Club